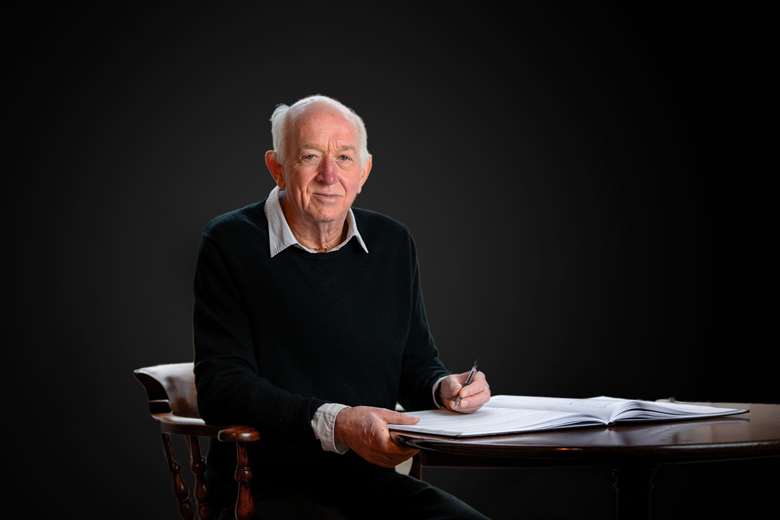

Composer Michael Stimpson on maintaining a music career after a life-changing illness

Michael Stimpson

Thursday, September 7, 2023

After his vision was damaged by a rare virus in 1976, Michael Stimpson didn’t let his loss of sight derail his musical career. Now celebrating his 75th birthday with the release of a seven-disc box set of his work, the composer looks back on the motivations and coping mechanisms which allowed him to remain resilient in the face of adversity

On Christmas Day 1976, at the age of 29, I lifted a cup of coffee to my mouth and, rather oddly, it missed my face. Feeling extremely unwell I was admitted a few days later to Charing Cross Hospital in London where it was established that I was suffering from a rare virus, Guillain-Barré Syndrome. Shortly after New Year’s Eve I was taken to the intensive care unit where I spent over four months unconscious and totally paralysed. When I was awoken, as I occasionally was, I found that I could only see a very little, and I have been registered blind ever since. I have occasionally been asked to write about these extraordinary events but, being a composer, I wrote a piece of music instead. This work, Tales from the 15th Floor, recorded with Karen Stephenson (cello) and Sophia Rahman (piano) will be released this October as part of a seven-CD box set marking my 75th birthday. Alongside recordings of my work by the Philharmonia Orchestra, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Allegri Quartet, and Roderick Williams/Sioned Williams, the box will also contain another new CD, Reflections, recorded by the Aquinas Piano Trio.

All this seems far away from the day in 1977 when I was slowly adjusting my wheelchair in front of a broken piano in the hospital chapel and waving a shaking hand to try and press a key. That day I had been given a white stick and been told that telephone operating or piano tuning were the two main jobs that I should consider. I decided instead to try and return to my musical profession as a classical guitarist. I was sent to the RAF where they had a leading hand specialist and gradually my body movement returned. All this culminated in my entering the Royal Academy of Music’s Advanced Course some years later. But while that was a substantial achievement, it also made it clear that high-level performing was not going to be an option – not because of any eyesight issues but because one finger had a permanent tremor and because I needed to take split second rests at manageable points in physically tiring pieces.

"These life events have had an influential and positive role on my writing."

I was aware of two abiding feelings resulting from this illness. The first was a wonderful sense of calm and peace of mind (I wish I had it now), and the second was a driving force to move on. This had much to do with the dedicated care that had enabled me to survive, and from the fact that I held no anger or bitterness over what had happened to me. This helped me through the recovery process, particularly when dealing with the severe pain which I experienced for some 10 years. Longer-term help was pretty much non-existent. At that time being registered blind just provided me with a bus pass and a talking book machine but as technical innovations came along, so did the Government Access to Work scheme, and undoubtedly my work could not have developed without the assistants that that scheme afforded me. In fact, there was a third outcome that I didn’t notice at the time – I began to think differently, and in particular, more creatively.

I began with a thesis at the Institute of Education, written four words to a page with a large felt tip pen. Then, once computers with speech software began to emerge, I embarked on a series of articles, books, and music editing, mainly with Oxford University Press. By my early 40s I longed for a direct emotional connection with music, and so began a Masters and Doctorate in composition before beginning to focus on works for public performance.

But my musical life had one more twist. In 2011, I was approaching the end of two years spent writing my opera Jesse Owens, when I was told that I had an extremely large brain tumour which needed operating on as soon as possible. So, I wrote for every hour I could, completed the work on the Saturday, and entered hospital on the Monday. The surgeons tried to save the hearing on my right side, but this was not possible as the tumour was wrapped around the auditory nerve. I was left with hearing on one side only, which meant I lost directional hearing – not so good without useful vision. Gradually, however, the sound explosions in my head diminished, I became used to mono listening, and instruments began to regain their normal timbre.

When working, I have my eyes about six inches from a large computer screen with the note heads one to two inches in size. This allows me, just about, to get the five lines of the stave on the screen at once. I use headphones to tell me where I am as shifting from instrument to instrument on a larger score, or whilst building an orchestral chord, can be quite laborious. In general, I plan for some 15 editing stages, from the early draft which I politely refer to here as basic, to the final revisions that draw out those issues that you hope would go away, but haven’t. Recordings are of course edited in collaboration with those involved, particularly Classic Sound, my preferred company for recording, and this overcomes any hearing issues.

I am reluctant to offer advice – how one deals with something is very personal and dependent on many factors. Recovering from loss of eyesight was helped by having many other health issues to deal with and considerable personal support. Being a younger person with most of life ahead, enabled a positivity, which was there too after the tumour. Each day was so encouraging and there was relief in surviving too of course. Certainly, these life events have had an influential and positive role on my writing. Without them I’m not sure that I would have become a composer. Far harder to deal with in music are the things you don’t control, such as funding and opportunity.

Michael Stimpson’s seven CD box set of Recorded Works will be released on 5 October. Stimpson is also set to mark the 70th anniversary of the death of poet Dylan Thomas with Dylan, a song cycle for baritone and harp, performed by Gareth Brynmor John and Alis Huws in Swansea on 4 November and in New York City on 11 and 12 November. The Swansea concert will also be livestreamed.

www.michaelstimpson.co.uk