Earliest Church of England anthem written by a woman discovered

Rachel Webber

Friday, December 18, 2020

Postgraduate student Rachel Webber explains how she discovered the hymn from 1785

When I began my research into the music of the 18th-century London charitable institutions as a postgraduate student of the University of York, I was amazed by the sheer existence of all-girl choirs in their chapels. What I certainly did not expect was to find music written for such choirs by a woman. We know extraordinary tales of musical nuns within the Catholic tradition, but it appears that the Church of England has similar tales of its own, in the form of the lesser-known musical role of women in the charity chapels of Georgian London. In a 1785 collection of music for the chapel of The Asylum for Female Orphans I was delighted to encounter an extended setting of the familiar While shepherds watch’d text, entitled ‘A Hymn for Christmas Day’ and composed by a ‘Miss Savage’.

Jane Savage (1752/3-1824) has already received some scholarly attention; she was a composer of vocal and keyboard music which was most likely performed in her Holborn family home. She was the daughter of William Savage, a prominent musician in London and friend of George Frideric Handel. Her composition for The Asylum is her only surviving religious composition, having gone under the historiographical radar until now. This piece, composed for and performed by the girls’ chapel choir of The Asylum for Female Orphans, lays claim to being the earliest surviving example of a female composer writing an anthem for use in the Church of England. So how was it possible for a woman to compose in a religious context and society dominated by men?

How was it possible for a woman to compose in a religious context and society dominated by men?

The Asylum for Female Orphans (f.1758) was one of several charitable institutions founded in London during the 18th century, as society attempted to confront the poverty found in the lowest strata of society, with an intention of saving souls through regulated discipline and religious instruction. These institutions received the support of notable bishops, and chapels were quickly erected, and it was these chapel services that provided unique and significant musical opportunities for girls and women as singers, organists and composers. Members of high-society were often attracted to the spectacle of such chapels, where it was also possible to demonstrate their philanthropy. The Asylum was intended to shelter and educate orphaned girls between the ages of nine and twelve, protecting them from the dangers of living homeless and bereft of family. Another institution was The Magdalen Hospital, also founded in 1758, for penitent prostitutes. As in The Asylum, the Magdalen girls would sing for the chapel services, though in this institution they were hidden by a screen in the gallery. Similar institutions had already found favour and success in France and Italy, and the founder of the Magdalen Hospital Robert Dingley was directly inspired by these precedents. Another woman composer of the time, Maria Barthelemon, wrote music for use at both the Asylum and Magdalen Hospital, and her ambitious music deserves to be better known.

Two children are brought to the nurses of the Asylum for Female Orphans, Lambeth, London. Painted by T.S. Duché, engraved by Wm. Skelton (c.1778-1810). Wellcome Collection. License: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0).

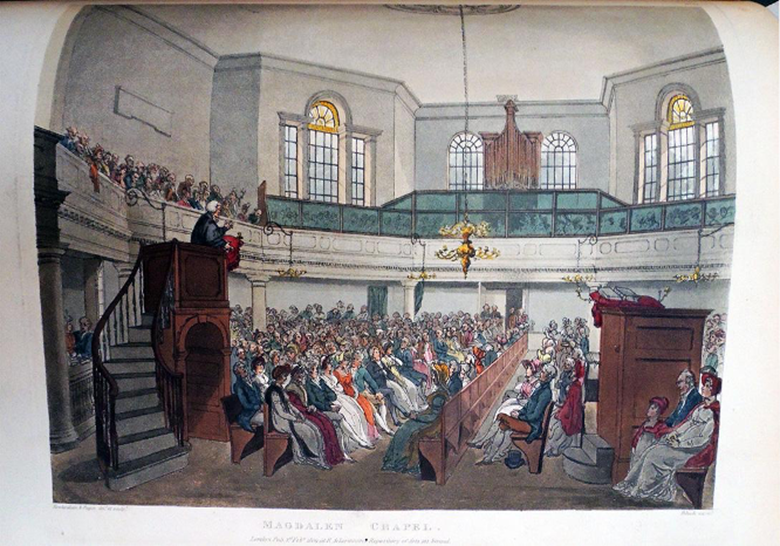

The interior of the Magdalen Chapel at St George’s Fields, from Rudolph Ackermann’s Microcosm of London (London: published at R. Ackermann's Repository of Arts, 1808-10).

Young girls also sang alongside boys in the musical performances of the widespread London charity schools. A large annual festival service featuring the charity school children singing together began in 1704, and from 1801 this was held in St Paul’s Cathedral, with an estimated five to eight thousand children in attendance. Both Haydn and Berlioz recalled their delight upon hearing the children perform having attended this service during their stays in London.

Robert Harvell, ‘The Anniversary Meeting of the Charity School children in St Paul's Cathedral,’ 1826, Museum of London Print Collection.

Many of the clergy in the charity chapels admired the progressive thinking and style of worship of the non-conformist theologians, and so welcomed and encouraged a musical style which was quite at odds with the more retrospective style embraced by the traditional all-male establishments in London. All the extended pieces in the Asylum collection (which we would today call anthems, but were originally labelled as hymns for their use of hymn texts) follow a similar format: they open with an organ introduction to introduce the main melodic theme, feature vocal sections with figured-bass accompaniment and occasional organ interludes or ‘symphonies’ as they were called, culminating with a section of buoyant Hallelujahs, all in a forward-looking galant style. This music reveals the high standard and competency of the girls as musicians, who clearly reached a similar standard of musical performance as the boys in the major London cathedrals and chapels, and it is to be hoped that the music by Savage and Barthelemon, and any other female composers waiting to be discovered, will soon acquire equal recognition alongside the music by their male contemporaries.

To purchase a copy of the newly-published edition of Whilst shepherds watch’d their flocks by night, click here.

The video below shows the piece being performed by the Ely Cathedral Girls’ Choir.