Baluji Shrivastav on how the music industry can support blind artists

Florence Lockheart

Tuesday, February 18, 2025

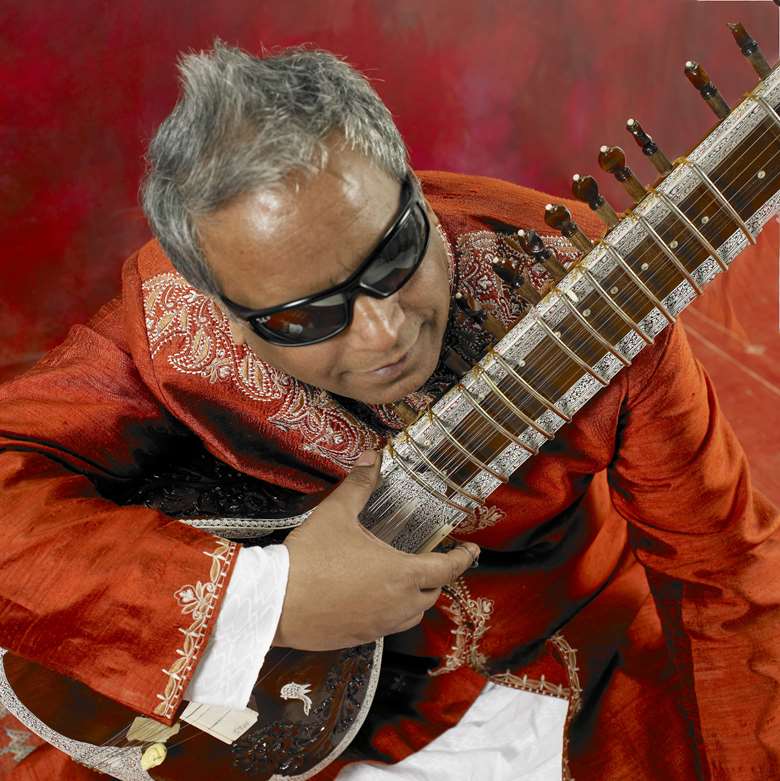

Indian multi-instrumentalist and Baluji Music Foundation founder Baluji Shrivastav OBE sits down with Florence Lockheart to discuss the hidden hurdles facing blind musicians and how the music sector can support its blind and partially sighted members

Blind musicians face unique challenges. Can you talk more about these hidden career hurdles and how you approached them?

Blind people are often put in a ‘disabled box’ alongside people with lots of different disabilities and access needs – this doesn't really work. A major assumption I encounter as a blind musician is that people tend to assume hiring us will be double the expense for them because we need an additional person to accompany us and so blind people can often fall to the bottom of the list. But this is not true; there are lots of organisations who help with our access requirements like the Arts Council and the Musicians’ Union. I also work with accompanists who are frequently able to help, and friends can volunteer to support blind musicians too, helping us with everything from finding our microphones to navigating hotels while touring.

In 2008 you established the Baluji Music Foundation. How has the foundation grown since then?

I launched the Baluji Music Foundation because I was struggling to find help with my career so I thought, ‘Charity begins at home, why not start here?’. We organise lots of things like workshops and dance events, but our main project is the Inner Vision Orchestra, the world's only professional ensemble of blind musicians which brings blind people from all over the world together in London. Our first show was very easy for me to organise; I asked each musician to share a song from their country, and we all learned and played it. The shows have continued in this way, the ensemble is growing, and we have toured all over the world.

"The sector should open the door to us and give us the chance to record, perform and participate"

Our recent projects include Blind Spot, which gives blind musicians a chance to meet for lunchtime concerts every week, where they can play without anybody's help. Another project we’re working on is Dot Aware, a wearable braille device allowing blind musicians to read music without using their hands while they are playing their instrument, feeling the music on their arms or neck. The project is funded by Nesta and we’re working in partnership with Queen Mary University of London, and we’ve already created a prototype. Technology has advanced so much, so there's less and less problems for blind musicians. Hopefully by the 2029 or 2030, we will be much more efficient.

'We are still stuck in that "disability box"; we perform at events like the Paralympics, but we should come out of that box and work in the mainstream' © Simon Richardson

'We are still stuck in that "disability box"; we perform at events like the Paralympics, but we should come out of that box and work in the mainstream' © Simon Richardson

The topic of inclusivity in the arts is at the forefront of many minds in the sector at the moment. What do you wish those in decision-making positions understood about making the industry more accessible for blind and partially sighted performers?

We have got brilliant musicians – as brilliant as any sighted musicians – but unfortunately, in the UK, music has not been promoted for blind people that much. We have got Stevie Wonder and Andrea Bocelli, and in India, we had famous music directors like Ravindra Jain, but nobody knows enough about blind musicians in the UK.

The sector should open the door to us and give us the chance to record, perform and participate. Blind and not blind musicians should work together. I have collaborated with pop artists, dancers and theatres before, without mentioning that I'm blind; they just invited me, I went there, and I worked. Blind people can be very, very good musicians, and more people need to be aware of that. We can work together, hand in hand, but the industry needs to open the door for us.

"I always say, ‘bumping into people is a great pleasure’"

Since then, the orchestra has recorded on ARC/Naxos Records and performed across the world at events including the London Paralympic games – what is your advice for labels and events organisers looking to support, present and promote blind musicians and ensembles?

They should come to our Inner Vision Orchestra shows to see how we work. We can hear each other very well without seeing each other and we have worked with so many organisations, dancers and famous artists. They should come and find out for themselves how they can open doors for us.

When we perform or record, we work alongside sound and recording engineers. I wish people understood our experience here. For example, if you’re blind and someone puts a coffee in front of you, you don't know where it is, and the same goes for microphones. Additionally, most microphones are labelled by number, but as we aren’t able to see these labels, we might struggle to communicate what we need in terms of sound. Monitors can pose the same problem.

'Blind musicians still face the industry assumption that they cannot work alone' (Image courtesy of the Baluji Music Foundation)

'Blind musicians still face the industry assumption that they cannot work alone' (Image courtesy of the Baluji Music Foundation)

Networking is also different. Blind people, generally, will sit in on one chair without moving because they are afraid of bumping into people, but I always say, ‘bumping into people is a great pleasure’. That being said, I can’t see who is sitting in a meeting or a concert, so if people want to meet us, they should not be afraid to approach us. It could develop our network, or be the start of a wonderful collaboration.

I'm very proud of what Chris McCausland has done – I would love to meet with him, we could learn from him, and we should perform together. I felt that same pride when I was performing at the Paralympics in 2012. I was listening to the music with my headphones on while I played, but when I took my headphones off, I heard so much applause. I felt the same when we performed at the 2023 International Blind Sports Federation World Games in Birmingham. But we are still stuck in that ‘disability box’; we perform at events like the Paralympics, but we should come out of that box and work in the mainstream.

How does the touring experience change for you?

On our most recent tour we travelled together with 13 blind people all over your UK. We toured with volunteers, including my wife, and we have a sense of humour with each other that helps overcome the stigma. Just like any group, the Inner Vision Orchestra needs to organise transport and work with managers, and we would benefit from the support of an agent. I wish promoters and agents understood that we don't need anything special, we just need the chance to show we can do these things. For example, I once toured to Warsaw by myself (taking 10 to 15 instruments) and performed for 10 days there. I proved, then, that I can work and travel alone myself, but blind musicians still face the industry assumption that they cannot work alone.

We are not unique musicians, we are the same as everybody else. We won't have any problems if we are given the right tools.