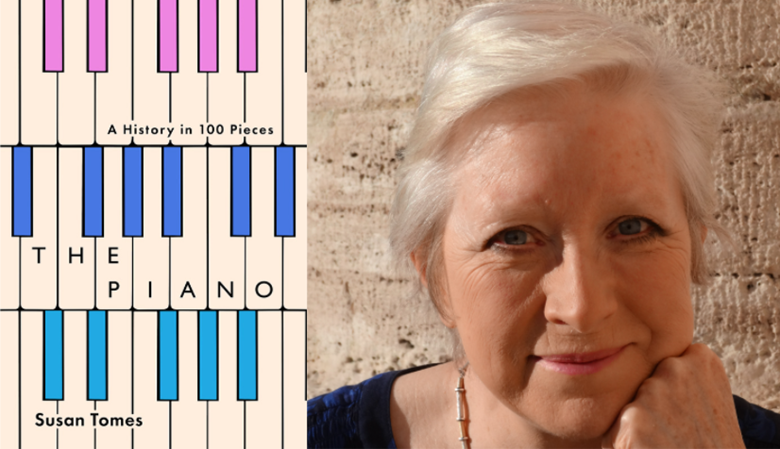

Book Review: The Piano – A History in 100 Pieces

Susan Nickalls

Wednesday, September 22, 2021

Susan Nickalls reviews Susan Tomes' journey through the history of the piano.

Yale University Press, Hardback £16.99

Susan Tomes

With a cheeky nod to British Museum director Neil MacGregor’s A history of the world in 100 objects, Susan Tomes traces the development of the piano through the composers who wrote for it in her latest book, The Piano – A History in 100 Pieces. Given that the popular keyboard instrument hasn’t essentially changed that much over the centuries, the focus of her highly engaging book is primarily on the repertoire. J S Bach didn’t see a prototype of what we would regard as a piano until 1736 when he was 50, but nevertheless his classic Goldberg Variations, written for harpsichord, is where Tomes begins her fascinating journey.

As a renowned pianist herself, Tomes is familiar with many of the solo pieces, chamber works, duets and concertos she explores and her passion and knowledge shines through. Her chosen pieces are inevitably personal and while she does tick the obvious Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, Schumann and Liszt boxes she also makes some interesting detours. Before her three chapters on Chopin’s piano music she looks at how the Polish composer was most likely influenced by the music of John Field - credited as the first person to write nocturnes for the piano - and in particular the pianist and composer Maria Szymanowska. Szymanowska was also from Warsaw and being 20 years older than Chopin, Tomes believes he must have come across her music.

'It is interesting that the genres in which Szymanowska composed – preludes, études, waltzes, écossaises, nocturnes, mazurkas, ballades and polonaises – were all genres embraced by Chopin. One of Szymanowska’s last compositions was the beautiful Nocturne in B flat (1831) written in St Petersburg. In melodic outline, decoration and formal shape it has things in common with Chopin’s Nocturne in A flat, Op. 32 No. 2 of 1837.'

'As a renowned pianist herself, Tomes' passion and knowledge shines through.'

While you could interrogate some of Tomes’ omissions – Charles-Valentin Alkan, Ruth Crawford Seeger and Nikolai Medtner for instance – Tomes does highlight some rarely performed pieces. These include Mily Balakirev’s Islamey: Oriental Fantasy Op.18 reputed to be one of the most technically difficult pieces ever written for the piano, Conlon Nancarrow’s Studies for Player Piano and Frederic Rzewski’s unusual but 'potent blend of lyricism and industrial process,' Winnsboro Cotton Mill Blues. Her well-researched and evocative descriptions make you long to hear these works played in the concert hall.

Tomes’ section on jazz music for piano almost demands a book of its own, ranging across Scott Joplin’s ragtime music and the Bepop pianists Bud Powell and Thelonious Monk as well as Billy Mayerl, Fats Waller and female jazz pianists Mary Lou Williams, Hazel Scott and Lovie Austin, to mention but three.

The final chapters on 'Today’s Piano Styles' and 'Tomorrow’s World', looking at where piano music might be heading, were also a bit on the light side. Surely Arvo Pärt, Philip Glass, Judith Weir and Thomas Adès are not the only contemporary composers writing for piano? What about Lera Auerbach, Morton Feldman and Graham Fitkin? Meanwhile Max Richter, Ludovico Einaudi, Terry Riley and Michael Nyman get only a passing mention alongside Brian Eno’s Ambient Music.

There is no shortage of piano repertoire for several follow-up volumes. And Tomes’ intriguing observations about earlier pianos having narrower keys more suited to smaller female hands, compared to the later instruments designed for the male span, is surely throwing down the gauntlet for someone to design and make a more female-friendly piano.

Buy the book here.