Funding focus: The Francis Routh Trust

Glyn Môn Hughes

Monday, February 19, 2024

Glyn Môn Hughes learns how the newly redefined trust has pivoted from concert promotion to giving grants designed to promote underappreciated composers

This article was originally published in our Autumn 2023 issue. Click here to subscribe to our quarterly print magazine and be the first to read our March issue features.

Anyone coming across the newly launched Francis Routh Trust will immediately encounter a strange paradox. For, while the trust is young – it is on the verge of announcing its first tranche of grants – it draws on more than half-a-century of significant musical history.

‘In terms of when it was set up, there’s a short answer and a long answer,’ says Simon Routh, chairman of the trustees. ‘The short answer is it was formally established by the Charity Commission in March this year. There followed a series of discussions with the trustees and we sent the formal press release out in May. So we’re young; we’re new.’

The trust, however, can trace its history from the late 1950s. Francis Routh, Simon’s father, along with colleagues Norman Tattersall and Roy Teed, all alumni of the Royal Academy of Music, planned concerts of music by British composers whom they regarded as being insufficiently performed or appreciated.

‘My father was a composer and an academic,’ says Routh. ‘He wrote various books and promoted concerts. He established a charity that he called the Redcliffe Concerts of British Music in the early 1960s. I think it was formally established in 1964. And through that charity he then put on a number of concerts, primarily in London.’

Those were in St Luke’s, Redcliffe Gardens, from where the charity took its name and the patrons were significant composers – ever heard of Sir Michael Tippett, Sir Arthur Bliss and Sir Peter Maxwell Davies?

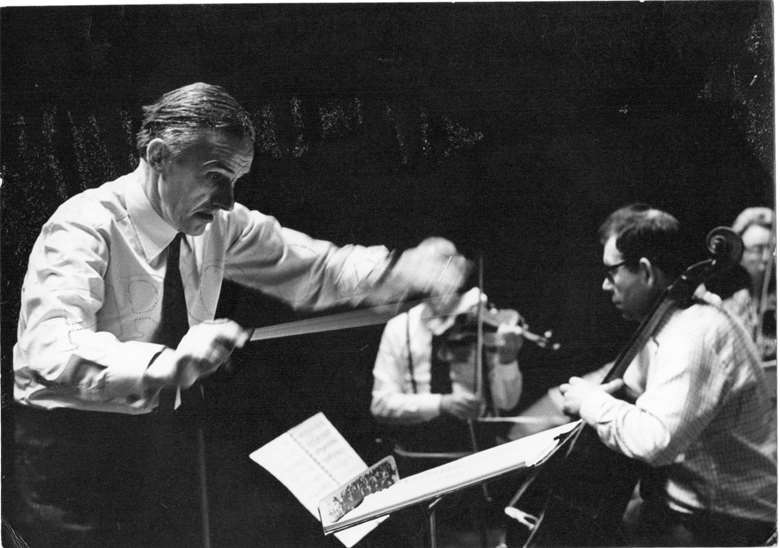

Key support: Francis Routh founded the Redcliffe Concerts of British Music, a precursor to the trust’s current activities © Courtesy of The Francis Routh Trust

Key support: Francis Routh founded the Redcliffe Concerts of British Music, a precursor to the trust’s current activities © Courtesy of The Francis Routh Trust

‘In its day – the heyday would probably be in the 1970s and 1980s – it was influential, especially in terms of the composers they involved,’ says Routh. ‘My father gave the first public concert of a work by someone called George Benjamin. Then there was Alan Rawsthorne, Priaulx Rainier, Alan Bush, Elizabeth Lutyens, Harrison Birtwistle, Tristram Cary, Andrzej Panufnik. He even put on the first concert of electronic music in the early 1970s.’

With the fallout following the abolition of the Greater London Council in 1986 affecting the capital’s musical life, the charity moved into making recordings rather than promoting concerts. In all, they produced 22 LPs and CDs and many of these are still available under the label of Redcliffe Recordings.

‘The Redcliffe Concerts charity still existed when my father died in 2021,’ says Routh, ‘and he left a legacy to the charity. Thank goodness, before he died we got a new body of trustees together and I took over as chair. After he died, with this legacy in place, the trustees then discussed what we should do. We felt that, rather than being a concert promotion society, we should change its role into giving grants to enable performances of British music.

"There are a number of trusts that focus on one composer, but I can’t think of any trust that focuses on second performances"

‘Given that we had quite a sizeable legacy, we thought we should also change the name to reflect the origins of the legacy, if you like. We also took the opportunity to change the constitution because it was a charity concerts society from the 1960s. As a result, it was a very old constitution. It was all completely legal but it would not really serve its purpose if we had a problem now. So we modernised the constitution, changed the name to reflect the provenance of the legacy – and those are the origins of the Francis Routh Trust.’

Apart from Routh, formerly a senior civil servant and now running a vineyard in Devon specialising in the production of sparkling wine, there are four other trustees. According to Routh, there’s good spread of expertise from the music world. Pianist William Howard is the performer and there’s the composer Freya Waley-Cohen. Dr Rupert Ridgewell, who is responsible for the printed music collection at the British Library provides the academic backbone and the quintet is completed by Robert Summers, head of the contemporary music editorial department at Faber Music.

How, then, is the Francis Routh Trust different?

‘The key words for us are “undeservedly neglected British composers”,’ notes Routh. ‘We don’t say no to new commissions, and we don’t say no to first performances, but our key raison d’être is a focus on composers who have had their first performances, but we are left asking why we have not heard more of them? Indeed, they don’t have to be living composers. There are some composers from the late 20th century – some great women composers, for example – and we must ask why they are not being heard.

‘There are a number of trusts that focus on one composer, but I can’t think of any trust that focuses on second performances. That’s what we do and we will also consider recordings or simply enabling performances. We even had in mind, at one point, to enable production of manuscripts for performances.

© Courtesy of The Francis Routh Trust

© Courtesy of The Francis Routh Trust

‘We do say that we focus on British music. By that, we mean those who were born here or who reside here, though we’ve not been specific about how that applies to Northern Ireland. My father was a great promoter of Panufnik, for example, when he came from Poland. Though he was a Polish national, he lived in this country and that was enough for the concerts society. And that legacy lives on in what we are doing now.’

The grants given are modest, since the trust lives off the income from the legacy, which amounts to around £15,000 per year.

‘We really need to say that the trust only started in May and we are in the middle of the first grant allocation,’ says Routh. ‘We have said that we would normally give grants of up to about £1,000. We are not being totally specific, and we would not preclude something more than that. But if we had this discussion in 12 months or two years’ time, it could well be that we have developed and changed focus.’

Expressing his surprise at how quickly the news about the trust got round the music world, Routh was particularly heartened by the 56 applications that came in for the first tranche of grants.

‘There included plans for some new commissions, there were proposed performances of composers from the late 19th century I’d never heard of, there were some recordings in there, some tours… it was a great mix,’ he said. ‘It was good to see that people were thinking creatively – I was surprised by the sheer amount of creativity that is out there. It has been really encouraging.

‘I put on some chamber music concerts here in Devon and we had a young quartet come down during the first week of June. They did not know that I had a connection with Francis Routh Trust and I asked them if they had heard of it. They had, so that really was heartening. The word has got out and we have had a really great response in terms of this first grant round, which closed at the end of July.

‘Now whether those 56 applications came about solely as a response to the fact that we have just launched, I am not sure that is the case. The vast majority are for the window of opportunity between October of this year and March of next. If it was a one-off response, I’d be looking at a much wider window of when things were being planned, so I think that bodes well for the future.’

There is a comprehensive website which has been produced by the trust and application conditions are made clear there. There is also a single sheet application form. Deadlines for applications fall at the end of January and July. The trust aims to come to a decision on the award of grants within approximately two months. The website also includes details of the trust’s fascinating library, which is a gift for musicologists as well as a shop selling recordings and sheet music.

‘I must emphasise that the response we have had so far is great, especially seeing how quickly it all got going,’ says Routh. ‘But it’s very much a work in progress. While I have looked at the applications, it will be interesting to see which way the trustees will go. Of course, inevitably, there are more applications than the number of grants available. Whether we go with smaller grants for a larger number of organisations, or whether we focus down on one particular area in future is something which remains to be seen.’