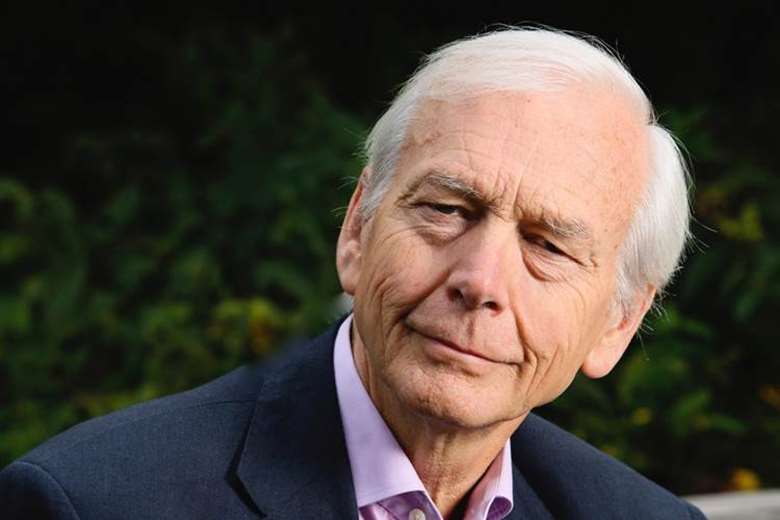

John Humphrys: ‘You don’t need to be an expert to admire a great symphony’

Jon Tolansky

Wednesday, November 22, 2023

The former BBC broadcaster turned Classic FM presenter and passionate classical music advocate, talks to Jon Tolansky about the musical moments which shaped him

‘Classical music is a unique form of sharing and communication’. The words, not of a professional musician, but of a distinguished and highly respected broadcaster famous for a very different sphere of communication: investigative interrogation. After 33 years of presenting daily news and current affairs on the BBC’s flagship Today programme, John Humphrys now has a weekly radio programme sharing his love of classical music with listeners to Classic FM. Exuding passion and care in all his communicating, his presence at Classic FM is an important advocacy for classical music.

His quest for truth as an interviewer on the Today programme garnered a prodigious loyal following, as have the eight books he has written. Two of them, Lost for Words and Beyond Words, examine the way in which we use – and sometimes abuse – the English language. He believes our language is not only something to be treasured and protected but also something that enriches our lives in ways that are difficult to measure. He finds parallels between the beauty of language and the beauty of classical music. That helps explain his heart-felt fervour for the music he introduces on his Classic FM programme, which he hopes will attract yet more people to classical music.

“I had spent my life from the age of fifteen in the business of communicating. Isn’t music a form of communication as well?”

Like all the finest communicators his ardour belies his age. Having just recently celebrated his 80th birthday, he sounds as youthful and vigorous today as when he interrogated Margaret Thatcher in her first years as prime minister. His own story of classical music in his life has a particularly important overtone for today’s debates about availability and accessibility. He told me that he himself might not have discovered it but for a chance encounter.

‘I never had any exposure to classical music until I was in my late 20s. Until then classical music occupied a distant, almost unknown world from the environment in which I grew up. My family was very poor. We lived in Cardiff in what would now be called a Cardiff slum. There was an outdoor lavatory, newspaper instead of toilet paper and we all had to wash in the kitchen sink. We did have a radio – a ‘wireless’ as we called it – and it was almost permanently tuned to what was then the BBC Home Service. I didn’t even know the Third Programme and classical music existed! But we did listen to some music, or at least my father did. On Sunday evenings he would tune in to the Light Programme for Sing Something Simple, which ran for 42 years! When I was about thirteen, we managed to acquire a wind-up 78 rpm gramophone. I saved up to buy my mother a record of her favourite song: Harry Belafonte singing Mary’s Boy Child. She played it endlessly. As for orchestral music: I’m not sure I even knew what it was!

‘I left school at fifteen to work on a tiny newspaper in Penarth which also published the short-lived Cardiff and District News. I was appointed editor (so-called!) of its ‘TeenAge Page’ and exploited my grand title to get free tickets to every pop concert in town and even, occasionally, interviews with stars like Cliff Richard and the Everly Brothers. At seventeen I left home to work on a bigger weekly paper in Merthyr Tydfil. It was then, thanks to a friend called Ieuan, that I discovered mainstream jazz. He was fanatical about it. His ultimate hero was Duke Ellington – and I could see why.

“Classic FM gives its listeners what they want without in any way patronising them or making them feel ignorant”

‘I went to almost every concert he gave in this country and, some years later, in New York. He was a musical genius – as composer and conductor – and if anyone can be said to have inspired my love of ‘real’ music it was the Duke and, of course, the great Ella Fizgerald. I once managed to get into her dressing room before a concert hoping for an interview, but I clumsily smashed a mirror and her minders threw me out!’

John insists that he still loves mainstream jazz but it’s clear that once he ‘discovered’ classical music he realised that something had been missing from his cultural life and this was it.

‘It was an epiphany that I’ll never forget. I was at my home in Washington in the days when I was the BBC TV News correspondent for both North and South America, and my cameraman, a lovely chap called Bob Grevemberg, came over for supper bringing a CD with him, which he forced me to listen to. It was Beethoven’s Violin Concerto. I was transfixed. I thought the slow second movement was the most surpassingly beautiful piece of music I had ever heard. I still do.

‘With the door to classical music now opened to me – or at least ajar – my next memory was, once again, a slow movement by a musical genius. This time it was Mozart’s 21st Piano Concerto. I was hooked. I’d like to boast that my tastes in classical music have become infinitely more sophisticated over the decades, but I’m not sure that would be true. Then again, I’m not entirely sure what ‘sophisticated’ means in this context. Can anyone – even the most ‘sophisticated’ – deny the genius of Beethoven, Mozart, Bach, Tchaikovsky, Chopin, Brahms, Brahms, Schubert, Debussy etc? Obviously not. But equally obviously I respect the views of those who find great beauty in atonal music. Sadly, I’m not one of them. Perhaps if I’d been introduced to it at an earlier age my tastes would have been different. Who knows?’

“No presenter can stuff their programmes with all their own choices. Quite right too!”

It was that ‘epiphany’ that answered an important question for John. What would he do once he had left the Today programme? After all, it had dominated his professional life for 33 years. The idea of retiring was never on the cards – but he was equally adamant that he would not return to news broadcasting. He wanted something different. And when Classic FM approached him, he did not hesitate.

'Who wouldn’t prefer to listen to Beethoven as part of his day job rather than, say, Boris!’ © Global

'Who wouldn’t prefer to listen to Beethoven as part of his day job rather than, say, Boris!’ © Global

‘I leaped at it’ he told me. ‘Why wouldn’t I? I had spent my life from the age of fifteen in the business of communicating one way or another. Isn’t music a form of communication as well? It’s true that it appeals most directly to the emotions, but it goes way beyond that. You don’t need to be an expert to admire the structure and intricacy of a great symphony or concerto. You might even argue that it is the purest form of communication. And anyway, who wouldn’t prefer to listen to Beethoven as part of his day job rather than, say, Boris!’

But why Classic FM rather than any other music station? ‘That’s easy’, says John, ‘Classic FM gives its listeners what they want without in any way patronising them or making them feel ignorant if they happen to prefer one genre of music to another.’

One example John quotes is film music. He confesses: ‘I’d always been a bit snooty about movie scores it – but that’s because I suppose I didn’t properly listen to them. But the Classic FM audience does and when I started doing the same, I realised what I had been missing all those years. There’s some wonderful stuff out there. John Williams and Ennio Morricone, to name just two, may not be Beethoven and Mozart but they are geniuses in their own field.’

“I saved up to buy my mother a record of her favourite song: Harry Belafonte singing Mary’s Boy Child. She played it endlessly.”

John’s other ‘confession’ is that he had underestimated the appeal of a station that devotes itself entirely to classical music. ‘I am constantly surprised by the number of friends and acquaintances who casually mention that they’d heard me presenting my Sunday afternoon show or standing in for Tim for the breakfast show. And not just people of my own generation: young people too. If you had asked me a few years ago to define the typical Classic FM listener I would have struggled a bit but now I think I’d answer that there is no such thing as a ‘typical’ listener. It could be anybody!’

What’s clear from talking to John is how much he himself enjoys his ‘new’ job after a lifetime broadcasting news and current affairs and winning just about every award going. ‘It’s partly because of the people I work with. The producers and researchers are phenomenally helpful and clearly love their work. That shows. Enthusiasm is everything… well almost everything. Many are also incredibly knowledgeable about music. I’m learning a lot from them! In fact, I’d go further: I’m discovering things about great music that have changed my own approach. ‘

So does all that mean he now gets to make all his own choices when it comes to his own programmes? John laughs at the idea.

‘Fortunately for the audience the answer to that is no – but I do get to influence the choices. The first time I met my producers they wanted to know if I had any favourite composers and, of course, I told them. But they made it clear that no presenter can stuff their programmes with all their own choices. Quite right too! After all, if you’re a station broadcasting twenty four hours a day seven days a week you must guard against too much repetition. I might personally be very happy with endless repeats of the Beethoven Violin Concerto but I suspect the audience might have other thoughts.

“I am constantly surprised by the number of friends and acquaintances who casually mention that they’d heard me presenting my Sunday afternoon show”

‘The other enormous factor – and it’s one of the greatest achievements of Classic FM in my view – is the Classic FM Music Hall of Fame. A huge amount of time and effort is devoted to establishing the 300 pieces of music the audience most appreciates and it’s an absolutely vital tool in constructing programmes that most people will love most of the time. And we know that’s the case because they themselves have made the choices and the chart is updated every year.’

When I asked John for his own favourite ‘musical memories’ of his life he recalls two. One was his involvement years ago as patron of the Pendyrus Male Voice Choir, one of the most acclaimed in the world. He said: ‘There was something about a Welsh miners’ choir that is intensely emotional. I’d been down deep mines when I was a young reporter and seen for myself how hellish it is at the coal face. You wonder how anyone could spend more than five minutes breathing in all the filth and facing the ever-present danger of a collapse. Many miners died. I was in Aberfan a few hours after the terrible disaster of 1966 when a coal tip crushed the village school and 116 children died. I do not mourn the passing of mining in the valleys, but I do miss the concerts of those wonderful choirs. To see those men on stage singing proudly in their crisp white shirts and smart blazers, but with the veins in their hands stained with coal dust, brought tears to my eyes. This truly was the power of music.’

His other memory was more personal: sitting in the front row of a concert hall forty years ago watching his cellist son giving his first solo performance. It was the Elgar Cello Concerto.

‘I was so nervous for him I couldn’t stop squeezing my arms. I still bear the imprints!’ In so many ways, presenting a Classic FM programme for John is not so much a job as a gift. Music has been a transformative influence in his life. There are many who will say: long may it remain so.