On with the show: Inside the world of stage management

Charlotte Gardner

Monday, November 11, 2024

Unpacking the tour bus, cueing scene changes, running the rehearsal room and reviving exhausted opera singers – stage managers are essential to a successful performance, finds Charlotte Gardner

This article was originally published in our Spring 2024 issue. Click here to subscribe to our quarterly print magazine and be the first to read our January issue features.

You know that old adage about how you can’t be everything to everyone or you will be nothing to anyone? Well, anyone who has ever stood in the wings of a major concert hall or opera theatre, preparing to walk out and deliver a stage-commanding performance, will know of one particular classical music career to which that rule does not apply. They will know that, while as a performer you have to believe that the stage is yours when you’re out there, the reality is that the stage emphatically does not belong to you and nor can it; that a whole host of outside elements need to come together before you can jump into the spotlight, from the house and stage lights being all set, and any live broadcast team ready, to your musical score or vital prop waiting for you in the right place – and that the means to track or manage all or any of the above is entirely beyond your capability. Thankfully though, there is someone who knows precisely where everyone and everything is, and who will be cueing you at exactly the right time. They’re probably already standing calmly by your side, making the final necessary checks while simultaneously pre-empting your desire for a final sip of water, or gauging whether you’re the type who needs personal space in these last moments, or a quick nerves-dispelling joke. This person is the stage manager.

‘The stage manager is a person who has the overview of all the different elements of a production and is responsible for ensuring that the show goes up on time, and runs as it should, with everyone safe,’ summarises Emily Gottlieb, incoming executive director of Longborough Opera Festival, outgoing chief executive of National Opera Studio, and formerly a stage manager at the Royal Opera House for 15 years.

Emily Gottlieb: ‘The go-to person, giving as much information to as many people as possible’ ©Gail Fogarty

As for how you become one, for Gottlieb it all began in the 1990s when, studying singing at the University of Birmingham, she realised that there were other singers who would probably get further than her. Knowing equally that her career was going to be in opera, she asked her singing teacher, who was then running Mid Wales Opera, for a job. ‘She said I could be a member of the chorus and pay them twenty-five pounds a week, or I could be an assistant stage manager and they’d pay me two hundred pounds a week!’ remembers Gottlieb. ‘So being a poor student, I went for the latter. I was very green, but I loved it. I understood what singers need and how to help them. I also liked working with props – my father was a lute maker, I’ve always been interested in making, and in fact I thought that perhaps I was going to be a designer or even direct. So stage management appeared to bring together all the elements I was interested in – technical knowledge, but also skills that are rather more personal and empathetic.’

As for what a day in the life of an opera stage manager might be, if you’re starting out and perhaps working on a fringe show in a pub theatre, says Gottlieb, you’ll be responsible for everything from sorting props and getting costumes, to marking out the stage and making sure people know where to go. You’ll also run the rehearsal room, making sure people are there on time, break on time and get a proper break. You’re probably also the assistant director, and running the lighting. At Covent Garden level things both shift and expand. ‘There, you’ve got a deputy who will be running all the cues for lighting, sound and anything technical, and communicating with the front of house,’ she explains. ‘But you are the central go-to person, giving as much information to as many people as possible, to ensure that the show runs smoothly, and making sure that everyone is doing what they should be doing, from the rehearsal room to the stage. There’s a lot of paperwork because technical staff have a cue sheet for everything, for instance pushing a truck on and off the stage. A wig department might need to know that the director has just said, “Angela needs a red wig for Act 3”. Or it can be that you’re flying in a very complicated sequence of walls that need a lot of rehearsal, and you’ve got to set that up. Score reading is absolutely vital, because you tend to use your score to cue people on and off the stage, and to cue the scenery. You also need empathy and understanding. I’ve literally carried singers off the stage at the end of the curtain call, because they’ve given everything to the performance.’

“I’ve literally carried singers off the stage at the end of the curtain call, because they’ve given everything to the performance”

All this is as much about safety as smooth running. Gottlieb remembers particularly vividly when the Royal Opera House re-opened in 1999 with a new production of Falstaff by the late Graham Vick with designer Paul Brown. ‘They decided to capitalise on all the lovely new stage machinery with a very complicated set, involving several different floors that all sat on top of each other, an inflatable bed, telescopic daisies, a fat suit for Bryn Terfel as Falstaff, trap doors that came up through three layers of floors, a tree that rose up through the floor with all of the chorus on it... It was very fulfilling, but if you gave a wrong cue in a scene change, and a floor moved before a trap door had passed down to the bottom with a very important singer on it, you could potentially have a very serious accident. So we had lots of people in different places making sure we had what’s called “clearance”.’

That’s opera. If it’s orchestral stage management you’re interested in, there are plenty of commonalities, not least the logistics planning, but also some distinct differences. Laura Kitson is stage and operations manager for the London Philharmonic Orchestra (LPO), and equally found the career by accident – studying music at Trinity Laban, she took a student job on the conservatoire’s stage crew alongside her studies, and enjoyed it so much that when she was graduating and a post opened to actually run it, she went for it and never looked back. This, she found, was a job in which she could work alongside the greatest musicians, playing a key role in enabling them to give their best onstage. And while for orchestral stage management, score-reading is most useful simply for advance warning on what instrumentation any concert will require, her musical training is as much in play as her empathy and diplomacy skills when it comes to breaking it to a conductor that a particular stage configuration might not work in the Royal Festival Hall space. ‘It can be tricky,’ she says. ‘They know what they want, so there is a sense of managing expectations, and ensuring they trust you. Artistically you know what they’re trying to achieve, so it can be about saying, “You won’t get that, but we could do this”.’

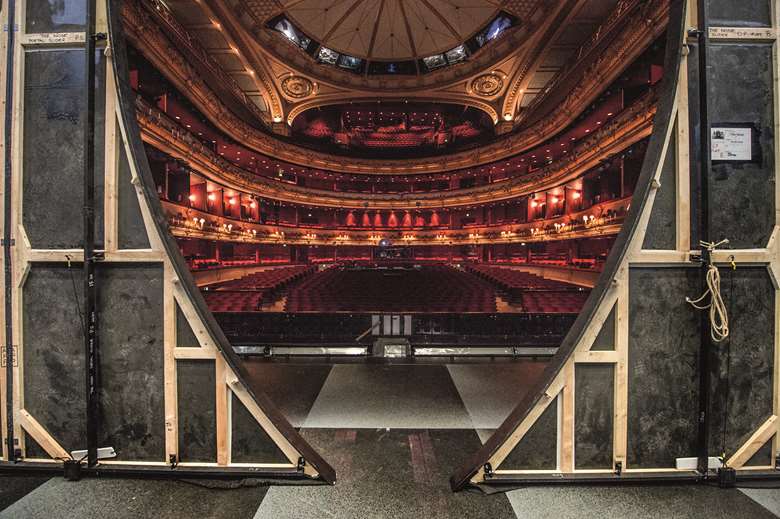

Unseen force: Stage managers ensure smooth performances at venues like the Royal Opera House ©ROH/Sim Canetty-Clarke

Touring is also a key aspect of the job, especially with London orchestras, which, if it’s a new venue, demands advance dialogue to establish things such as where the truck can park, what the load-in is like, and what the stage plan is. Although as Kitson points out, there’s only so much you can learn from a drawing on paper.

‘A lot of it is just walking in, being able to absorb a situation and adapt quickly.’ And yes, all this is quite physical work. ‘When touring you have to load and unload the truck every day,’ she says. ‘We also move every single person’s instrument, so there’s a lot of boxes.’ Another thing worth being aware of is that, even when on home turf, it’s a lifestyle choice as much as a job. ‘We are the first people there in the morning, and will be the last people there at night,’ she emphasises. ‘It definitely becomes a big part of who you are. We’re a big family.’

As for anyone putting on a performance without the luxury of an official stage manager, perhaps Kitson’s most crucial point is to think about how well your programme flows with regard to the stage moves. ‘If the overture’s six minutes long,’ she says, ‘and then re-setting the stage for the concerto is going to take eight minutes, that doesn’t make sense. People are watching you, and they’ve paid to come. At the LPO we plan it and practice it in rehearsal, so that it’s just as smooth as the performance itself.’ Opera-wise meanwhile, Gottlieb advises thinking about all the practical things you might need as a performer: ‘Then work out, if you don’t have help, how can you help yourself; and if you really need help, whether you can ask the venue for particular extra support, and be able to give information very concisely and easily.’

Do all that, and you might find yourself en route to a career in stage management; and even if you then decide, as Gottlieb did, that this is a stepping stone rather than the end goal, you’ll have made yourself eminently employable in the process. ‘If someone’s got stage manager on their CV, I’m often more likely to employ them,’ she says, ‘because I know that they’ll be the kind of character you always want.’