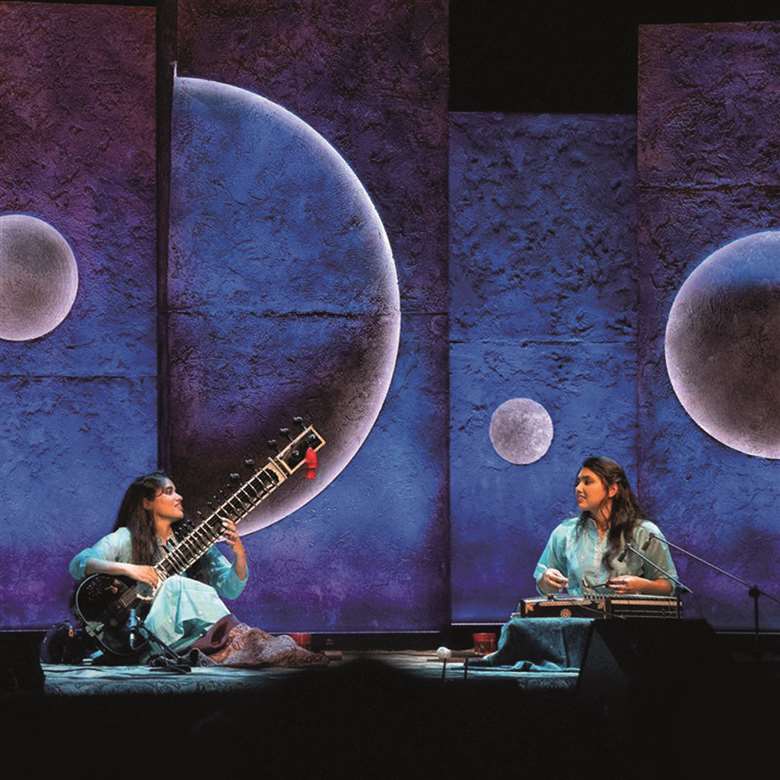

Raising the Darbar

Florence Lockheart

Tuesday, October 1, 2024

Darbar Festival has developed from a small Leicester-based event to a national treasure, bringing Indian classical music of all stripes to the Barbican every autumn. Florence Lockheart reports

Register now to continue reading

Don’t miss out on our dedicated coverage of the classical music world. Register today to enjoy the following benefits:

- Unlimited access to news pages

- Free weekly email newsletter

- Free access to two subscriber-only articles per month