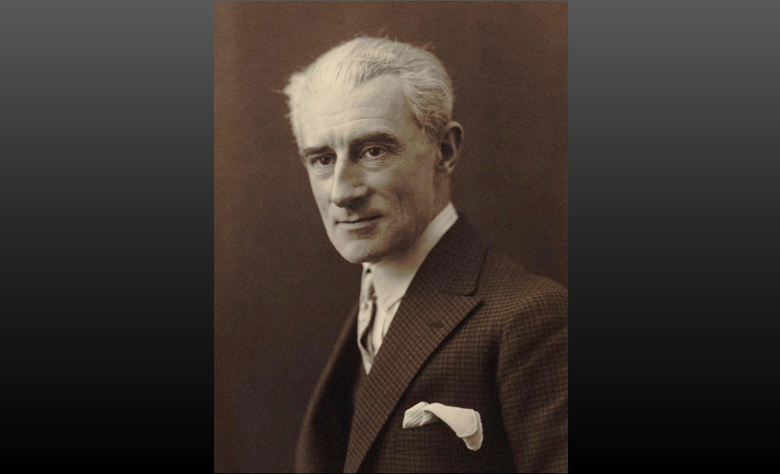

Ravel: The soul beneath the veneer

Jon Tolansky

Wednesday, March 19, 2025

Although Maurice Ravel was famously reticent about the meaning of his works during his lifetime, Jon Tolansky attempts to unpick some of the elusive connotations behind the self-effacing composer’s most well-loved works as we mark 150 years since his birth

‘A piece consisting wholly of orchestral tissue without music.’ That is how Maurice Ravel described his world-famous orchestral work Boléro in an interview with the Daily Telegraph in 1931, echoing a similar warning he delivered before its first performance at the Opéra de Paris in November 1928. Well, did he really mean that? Or perhaps more to the point, did he genuinely feel that there was no more to it than that? Maybe he did, and maybe Boléro’s mesmerising evocative power – if a performance truly does observe all his meticulous indications in the score – was nevertheless a relatively insignificant composition by his fastidious artistic standards, one which, as he went on to say in his interview, ‘should not be suspected of aiming at achieving other or more than it actually does’.

"Ravel’s personality was very complex – I have tried to study everything I could about him, and I think his character was mysterious"

That was Ravel speaking to the public, but he was generally taciturn about the meanings or associations behind his compositions, giving only occasional brief clues and, in rare instances, descriptions. He was generally more specific in denying possible or actual speculations, such as those surrounding Boléro and his mercurially elusive yet sumptuously multicoloured La Valse. In the case of La Valse, he commented that it was ‘a sort of apotheosis of the Viennese waltz, which I saw combined with an impression of a fantastic whirling motion leading to death. The scene is set in an Imperial palace around 1855.’ At the head of the score of this ‘choreographic poem for orchestra’, Ravel included a brief description of an imaginary scene, when he was hoping that the work might be taken up by Sergei Diaghilev for his Ballets Russes Company (Diaghilev declined, to Ravel’s disgust): ‘Dancing couples can be glimpsed intermittently through the swirling clouds. As they slowly clear, we see a huge ballroom filled by a circling crowd’. Ravel certainly could be graphically suggestive with words if he wished but, although he composed La Valse in 1920 not long after the end of the First World War, he categorically nullified any speculation that there might be an historical association with the War and the collapse of the old order in Europe. ‘It doesn't have anything to do with the present situation in Vienna, and it also doesn't have any symbolic meaning in that regard’ he declared in an interview with the De Telegraaf newspaper in 1922. ‘In the course of La Valse, I did not envision a dance of death or a struggle between life and death.’ Two weeks later he wrote to composer Maurice Emmanuel: ‘One should only see in it what the music expresses: an ascending progression of sonority, to which the stage comes along to add light and movement’. But what about the work’s ‘fantastic whirling motion leading to death’ – and the dissonant shock of the final whirling and whirling, faster and faster (‘Presser jusqu'à la fin’) up to the sudden catastrophic crash at the very end? Maybe this was nothing specifically to do with the War – but was it no more than ‘an ascending progression of sonority’?

It seems to me that Ravel as a man had consciously developed a veneer of almost nonchalance – perhaps to protect himself and conceal from the public his profoundly sensitive inner feelings. This artist of such high cosmopolitan sophistication, whose socially world-wise and internationally travelled awareness is mirrored so kaleidoscopically in works like La Valse, Rapsodie Espagnole and Boléro, was yet a private and in many ways withdrawn soul and very much a loner. He never married, but he loved children and animals – and some of his music presents a poignant escape back into childhood: with innocent simplicity in the fairy-tale suite Ma mère l’oye (Mother Goose), which he later extended into a ballet, and with intuitive fantasy and fragile vulnerability in the opera L’enfant et les sortilèges (The Child and the Magic Spells). He professed candidly about Ma mère l’oye, which he first composed as a piano duet for the two young children of his friends Ida and Cipa Godebski, that he was intending to ‘awake the poetry of childhood’. L’enfant et les sortilèges surely (although Ravel never said so) combines the astonishingly vivid suggestion of a child’s dream world with an overtone of profound tenderness in the child’s relationship to his mother. I am not alone in believing this reflects Ravel’s deep emotional attachment to his mother, whose death in 1917, when he was considering preliminary ideas for the opera, devastated him – just as the death of the librettist Sidonie-Gabrielle Colette’s mother a few years earlier had devastated her. Their mutual losses can indirectly be felt in the plaintive evocation of the Child’s growing loneliness and fear as the action of the opera progresses.

All that Ravel gave away to the public about L’enfant et les sortilèges was the enormous range of styles he incorporated into the various cameo scenes as everything the naughty child had destroyed in his room when he had thrown a tantrum suddenly comes to life: ‘There’s a bit of everything in it – Massenet, Puccini, American jazz and operetta, Monteverdi’, the composer said. But he was going far further than just pastiche. The animated fantasies of a child’s imagination are so realistically personified by the varying styles of the assaulted inanimate objects assuming differing living embodiments – the Armchair and the Sofa in an 18th Century sarabande peppered with occasional light sprinklings of jazz inflections; the Wedgewood Teapot and Chinese Cup dancing a foxtrot while berating the Child; the Child longing for the beautiful Fairy Princess, his first love, in a short aria reminiscent of Manon’s Adieu notre petite table in Massenet’s opera; the male black cat and the female white cat duetting in at first an almost Vaudeville style but later working up to a frighteningly lifelike screeching din; the animals, plants and trees in the magic garden who after punishing the Child, see his act of compassion and forgive him, singing ‘he is good, he is wise’ in a chorale that might perhaps have been composed by Monteverdi – these are only a few examples.

"We started the first movement. He clapped his hands right away: 'Too slow!' It was only a hair’s breadth too slow, but he wanted it just that shade faster."

It is in the profusely diverse guises of Ravel’s song creations that he most prolifically absorbed and understood the styles, sounds and, crucially, feelings of people in manifold places as varied as Spain, the Middle East, Greece, Madagascar, America, and of course France. Perhaps his lack of conscious autobiographical incentive was part of what led to his immersion in cultures and peoples around the world. His genius was the authenticity with which he evoked the sentiments of these cultures in works as fundamentally disparate as Vocalise en forme de habanera, which gives us the indigenous sounds and tonalities of flamenco singing in all its sadness and longing; Kaddisch, so uncannily capturing the depth of Jewish fatalism in the prayer for the dead and the mourners; and the Chansons Madécasses (Madagascan songs), in which he conjures up traditional Madagascan scales and colours that are aeons away from anything else he ever wrote. Although he denied any connotations, the second of the three Madagascan songs, entitled ‘Aoua!’ and opening with a violent dissonant shout ‘Aoua! méfiez-vous des blancs’ – ‘Aoua! Beware of white people’, certainly hints at the composer’s revulsion with the French colonialism of the time. Baritone Thomas Hampson agrees: ‘There’s no question that Ravel was making a political statement. He was making a very definite observation about the offence of the French Foreign Legion in the colonisation of lands and peoples that did not deserve this occupation. And indeed, it was altogether an observation to the effect that we should pay attention to how we treat people around the world.’

Ravel himself, though, would not state that explicitly: for him, his music and the poetic texts of Évariste de Parny would be saying everything. As was the case with nearly all his music, he had no desire to reveal anything personally about what he had written. Pianist Bertrand Chamayou, an acclaimed interpreter of all the composer’s piano works, goes a step further than even this in his appraisal of him, as he said to me in an interview a few years ago: ‘Ravel’s personality was very complex – I have tried to study everything I could about him, and I think his character was mysterious. I feel that in his music you can hear a base where his personality probably is, but it is difficult to say where it comes from. It seems that different pieces could have been conceived by a different person, and he is hiding behind, for example, the idea of transforming a Viennese waltz or a baroque dance such as in Le tombeau de Couperin, or being even more Spanish than a Spanish composer. It seems as though he was having a pretext that he could use like a mask’.

This barrier, however, was very swiftly removed when he was in the presence of the musicians who were rehearsing or performing his compositions. Without an ounce of hesitation or restraint, Ravel revealed his extreme displeasure if any detail of the most meticulously marked indications that he had put in his scores was not being faithfully observed – or, equally insufferable to him, if anything supplementary was being added, no matter how subtle. Back in 1997 the cellist George Roth, then 94 years old, recalled to me the occasion on which he rehearsed Ravel’s Piano Trio in the composer’s presence in 1928 when as the Budapest Trio he, his brother the violinist Nicholas Roth, and a guest pianist were engaged to play the work at a Ravel Festival in Paris: ‘We started the first movement. He clapped his hands right away: “Too slow!” It was only a hair’s breadth too slow, but he wanted it just that shade faster. Everything then went smoothly until the violin has the second theme… and my brother played it very espressivo. Ravel said “I don’t want that” – he wanted it played absolutely plain. He said, “Debussy and Ravel are their own best editors – you don’t have to add anything to what they have written”.’

"Ravel crystallises each syllable and gives each line and word musical rhythms that preserve Mallarmé’s – at the same time sparing him any vulgar melisma or false agogic"

This is a very illuminating insight into Ravel’s music. Like Verdi, and also like Stravinsky and Britten, he was ruthlessly draconian about his creations being played entirely exactly ‘come scritto’ (as written), and like them he disliked any excess of any kind. He clearly felt that playing that delicately wistful melody of the second subject with a strong espressivo tone was contrary to the nobly restrained nature of its pensiveness. And although he did not say as much to Nicholas Roth and the other members of the Budapest Trio, if he had felt like doing so, he could have cited that whenever he wanted an espressivo in his music he would indicate it – as indeed he does to such melting effect in the piano accompaniment to his Vocalise en forme de habanera.

As Bertrand Chamayou said, Ravel’s personality truly was complex – and a facet of this was his panoramic breadth of cultivation. In most of his music, certainly in the wake of his earlier works, he sought to distance himself from the powerful influence that symbolist poetry and theatre had exerted and continued to wield over many composers of his era. Yet, in 1913 he created his quintessentially symbolic setting of the poetry of Stéphane Mallarmé in his Trois Poèmes de Stéphane Mallarmé, in which a soprano and a small instrumental ensemble suggest the ambiguous world of the text with extraordinarily appropriate atmosphere. The conductor and writer Robert Craft said of this work: ‘Ravel crystallises each syllable and gives each line and word musical rhythms that preserve Mallarmé’s – at the same time sparing him any vulgar melisma or false agogic’ (The Nostalgic Kingdom of Maurice Ravel – New York Review of Books, 1 May 1975). Certainly, in the last of the three songs, Ravel strayed further from conventional tonality than he had ever previously done in his oeuvre, presenting a mystifyingly abstruse sound world that corresponds as masterfully to the essence of Mallarmé as did Debussy’s very different setting of the same poems in the same year. And for once Ravel himself was forthcoming – though about Mallarmé, not himself – in an interview with the New York Times in 1927, in which he said: ‘Mallarmé exorcised our (sic. French) language, like the magician that he was. He has released the winged thoughts, the unconscious daydreams from their prison’.

As Bertrand Chamayou said, Ravel’s personality truly was complex – and a facet of this was his panoramic breadth of cultivation. In most of his music, certainly in the wake of his earlier works, he sought to distance himself from the powerful influence that symbolist poetry and theatre had exerted and continued to wield over many composers of his era. Yet, in 1913 he created his quintessentially symbolic setting of the poetry of Stéphane Mallarmé in his Trois Poèmes de Stéphane Mallarmé, in which a soprano and a small instrumental ensemble suggest the ambiguous world of the text with extraordinarily appropriate atmosphere. The conductor and writer Robert Craft said of this work: ‘Ravel crystallises each syllable and gives each line and word musical rhythms that preserve Mallarmé’s – at the same time sparing him any vulgar melisma or false agogic’ (The Nostalgic Kingdom of Maurice Ravel – New York Review of Books, 1 May 1975). Certainly, in the last of the three songs, Ravel strayed further from conventional tonality than he had ever previously done in his oeuvre, presenting a mystifyingly abstruse sound world that corresponds as masterfully to the essence of Mallarmé as did Debussy’s very different setting of the same poems in the same year. And for once Ravel himself was forthcoming – though about Mallarmé, not himself – in an interview with the New York Times in 1927, in which he said: ‘Mallarmé exorcised our (sic. French) language, like the magician that he was. He has released the winged thoughts, the unconscious daydreams from their prison’.

Perhaps the metaphorical distance in Mallarmé’s poetry particularly appealed to Ravel’s inner privacy. His highly multiform range of creations, of which I have only touched on a very few here, might almost be the works of many different composers – except that despite all the striking individual worlds, the soul of Ravel is always there. Even though he told us little, if anything, about himself in words, beneath that prickly public veneer I think he revealed more about himself in his music than even he knew. This was an artist – and man – of immense sensitivity, inspired imagination, and, of course, masterly brilliance. 150 years on from his birth, it seems hard for us today to believe that in his lifetime, despite his enormous public success, he had to endure disrespectful cavilling from some of the critics in his home country (notably the disparaging Pierre Lalo). Deep down, Ravel was very hurt – but he would not exhibit it to the public. Beneath the mask, he was far too feeling to risk doing that.

All Images courtesy of © Wikimedia Commons